Written By Elke Riesterer

Odyssey Magazine, Feb / Mar 2007

I found myself pulled to visit Thailand. This country has a dwindling wild elephant population due to many depressing environmental circumstances, and the captive population is going through the harshness of an artificial life. As a body therapist working with all species, and with a special focus on elephants, I decided to contact the government-owned elephant conservation centre in northern Thailand to introduce hands—on touch therapy to the injured elephants at the centre’s hospital. I was thrilled they agreed, and so off I went to a land where elephants had a long cultural history.

There are over 50 working elephants at the centre. Some are used to provide elephant rides for tourists, while others perform tasks in an arena filled with spectators. There is also an elephant hospital, which is where I met Krungsee, a 40-year-old female elephant whose strength and perseverance in the face of adversity has really set an example for us all.

Krungsee’s head from trunk to ear is dotted with pink freckles. A fuzzy reddish string of hair crowns her large head and continues down her spine. When I met her she looked well fed and strong, but her injury was obvious and severe: Krungsee was a landmine victim. She had been a logging elephant at the time and was wandering in the nearby regions of Cambodia and Laos, where landmines from the reign of the Khmer Rouge and the wars in Vietnam still lie in waiting.

A mine does not discriminate. While the size of an elephant is formidable, the impact of the injury is no less traumatising: it affects both their physical and mental state, with sometimes fatal results. As their habitat shrinks, elephants are forced to walk further and further into new territory to scavenge for food, and these countries are still riddled with active mines. When Krungsee unknowingly crossed a minefield, the mine blew up under her right front foot. Fortunately, she survived this tragedy and, even after receiving treatment at the hospital for three years, the wound was still about an inch deep.

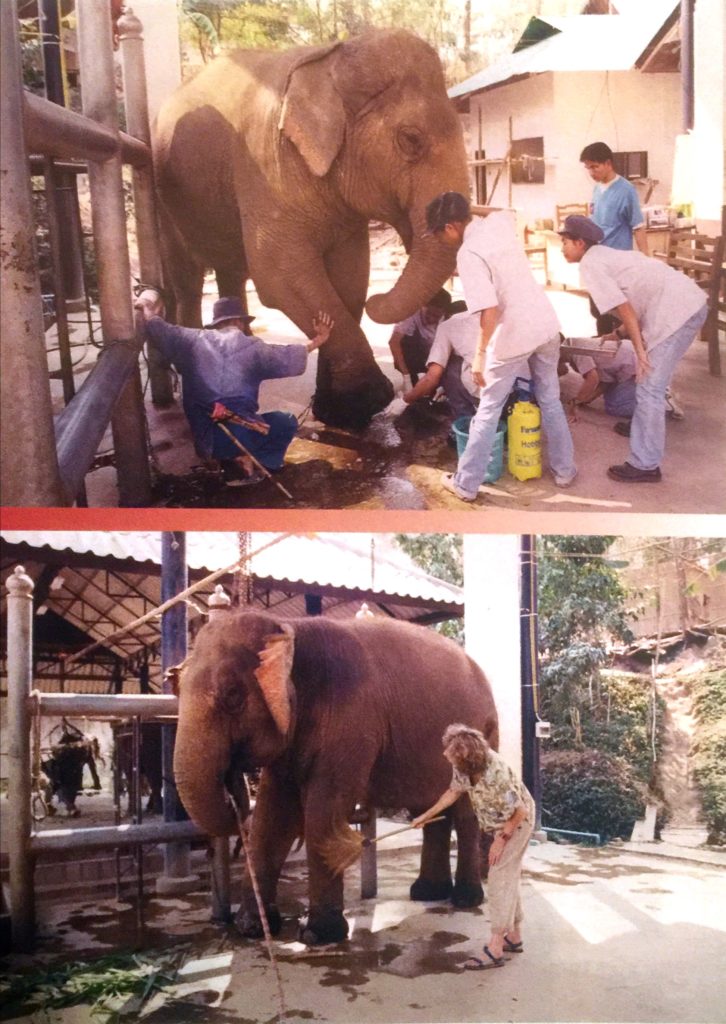

Krungsee’s routine at the hospital was a daily hobble down from her spot on the terraced hill where she was chained each evening, to the cement floor of the veterinarian station. Krungsee would receive a long disinfecting foot bath from the staff, and then was allowed to air out. She was loosely chained at the vet station for two to three hours before being bandaged again. It was during this time that I was given permission to explore what body therapy could do for her traumatised body.

As a result of holding up her right leg for three years, her muscles were significantly atrophied. The efforts of the hospital staff brought remarkable progress, but she still refused to put her right leg down for any amount of time except for short intervals or when she had to walk. Krungsee had perfected an unnatural accommodation to her injury that was making complete recovery impossible. I used a combination of acupressure and TTouch (Tellington Touch) along Krungsee’s spine to make her aware of her body again. I worked her shoulder girdle to help her lengthen the muscles she had kept contracted for so long. In between all this I stroked Krungsee gently with a soft broom for calming purposes and to give her a greater sense of her whole body. All the while I made sure I listened carefully to any body signals, so as to be ready to pause should the sensation have an adverse effect. Almost daily — while working with Krungsee — I became aware that the centre’s veterinarian Dr Tom had been watching me. Yet, each time my eyes glanced at him, he would quickly look away. I could sense his interest, but he did not speak or even say hello. Undeniably, elephant body therapy is a novel and challenging practice for people to embrace.

My new friend Krungsee was my companion guide into the geography of the Asian elephant. As my hand traveled and explored the vast territory of her stocky body, she would tell me what and where I needed to go. One such time was when I was stopped by her sensitivity around the belly area. She expressed her concern through body language by lifting her rear leg protectively and pulling it forward as if to cover her lower area so I could not touch it. With kind understanding instead of forcing the issue, I moved gently to her head where I let her feel a number of comforting circular motions around her mouth, jaw and eyes. This ended our session on the positive with a memory towards pleasure.

Krungsee and I established a daily routine and, gradually, she became accustomed to the various touch modalities. Krungsee showed her increasing appreciation of the touch by pushing back into my hands and letting her eyes partially close. I continued using the soft broom by stroking slowly across her body to further facilitate a new sense of body awareness. Krungsee had become very disconnected from the rest of her body while compensating for her injury. I was hoping that, after all the medical treatment she had received at the hospital, massage, TTouch, and acupressure would be able to overcome the now automatic response her body had developed to the injury. This was truly a case to be looked at holistically in order to heal the animal completely.

After five days of body therapy, Krungsee had her first breakthrough. I was able to release her leg muscles and shoulder girdle on her injured side to such a degree that she was able to stand on her foot. Words can hardly describe my excitement on that truly memorable day. She really had engaged with me during this particular session, pushing into my hands and lining up along the metal bars by the platform so I could climb up and use acupressure along her spine and upper scapula areas. I worked her left side as well, which had been compensating all this time for the injured leg and was very tense. While Krungsee continued to stand on the wounded foot, I rushed to share the exciting news with any vet on staff. I ran into Dr Tom in his office only to be met by a lack of response to my bubbling enthusiasm. So, I went straight back to check on my dear Krungsee again.

Here she was standing motionless on her foot as I joyfully sat down to observe her. I marveled at her ability to test and trust the long neglected recently lengthened muscles. After about 10 minutes, I walked back to Dr Tom, who had remained at his computer, and reported to him that Krungsee was still standing on her right front leg- ‘Oh, yes?‘ he said without looking up. It left Krungsee and me alone in our victory. I then tried to point out Krungsee’s success to the nearby mahouts, using signs and gestures as I could not speak their language, but they simply laughed at me and shook their heads.

After three years of the same daily routine at the elephant hospital, Krungsee had a familiarity with her schedule. When the time arrived for her bandages to be put on, she would know what to do and lifted her leg just high enough that the staff could apply dressing before following up with the wrapping material. At this junction Dr Tom finally came out of his office and I heard myself saying with a voice deeply roused by emotions, ‘Krungsee just stood for 30 minutes on her foot; you just missed seeing it.‘ I was still basking in euphoria of what had happened.

‘Good,‘ was all he could say and went on about his routine check up with her.

The following day Krungsee participated nicely in TTouch push up and release movements called ‘Python Lifts’, in addition to clockwise circles and acupressure on her right hip area. While working on the top of her back she actually wriggled with joy. She even allowed me to rock her back and forth, which was such a lovely sign of trust. When it was time to put her up for the night, I went along with her elderly mahout as he led Krungsee quietly back up the hill when all of a sudden he began shouting violently, upsetting myself and Krungsee, demanding her to walk faster. She actually responded with a warning sound, popping the curved end of her trunk in an unmistakable fast gesture onto the ground. Luckily this got the mahout’s attention and he went ahead mumbling something and letting the both of us decide the pace. Needless to say, besides plain human impatience, there was no to rush her. What else did she have to do?

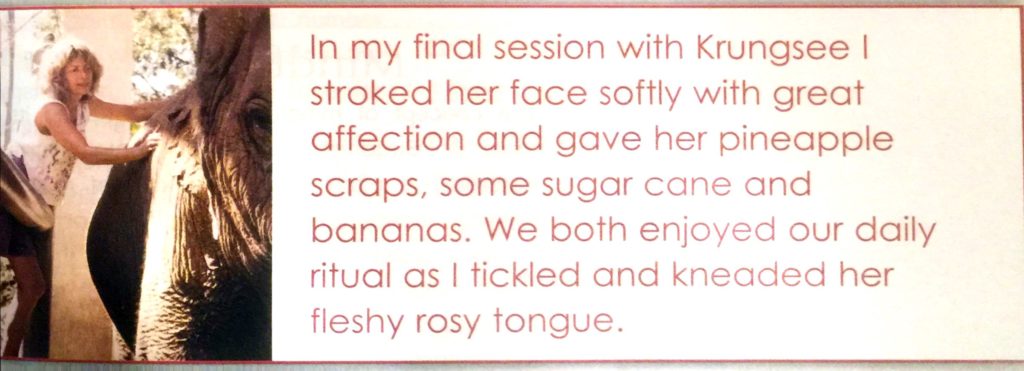

I had my final session with Krungsee three weeks later. I stroked her face often and softly with great affection. She had been given any food at all that day, and it was easy to see that she was a bit hungry. As she saw me approach, she opened her mouth in great anticipation. I gave her pineapple scraps, what sugar cane I could find laying around and bananas. We both enjoyed our daily ritual as I tickled and kneaded her fleshy rosy tongue while feeding her. Most of the elephants I worked with seemed to share the great delight of this particular oral sensation.

A busload of school children arrived at the hospital that day. They ran all around Krungsee as I worked on her, agitating her terribly. Sensitivity to an animal’s comfort level was obviously not a priority. But, Krungsee, despite all the distraction, still gave me such a heart of joy. She was standing now fully on both legs for even longer periods of time. Unexpectedly, and to my pleasant surprise, Dr Tom approached me after the children left and asked if I could train his tech assistant, Champoo, in the methods I had used.

‘Women are better with such things,‘ he explained.

Containing my disappointment that he had taken so long to express his interest made me appreciate what barriers needed to be breached. By now I had grown familiar with the reserved attitude of the staff. They had never before seen what I was attempting to do. Yet, I was happy to think that someone now might continue using body therapy with the big girl. I ended my session early that day to teach Champoo a few of the most effective movements on the elephant’s body. In the little time she had to practise in my presence she did quite well with the TTouch circles. Glad to leave on this responsive note, I made an effort to share with her all the changes I had seen in Krungsee. I asked if I could check on her progress via e-mail and Champoo said that would be wonderful.

I cherished my last precious moments with Krungsee, as I guided her up the hill, giving her tiny banana treats along the way. She was walking with renewed strength and confidence, leaving the hobble less noticeable to the untrained eye. In a last attempt, I tried to point this out to her mahout, but he was busy getting ready to chain her to her space. He used a hammer to pound the stake into the ground that held her chained in place. When finished he raised the hammer and rushed it toward Krungsee’s face as if to strike her between the eyes. I gasped in shock, but he did not hit her, choosing to stop at the last second. It was a joke. The mahouts watching nearby laughed.

As I walked alone back down to the hospital building I was deeply puzzled wondering what we as humans are doing? What does it take to break the pattern of unconscious abuse?