Written By Joan McL. Chesley / Modern Maturity

January-February 2001

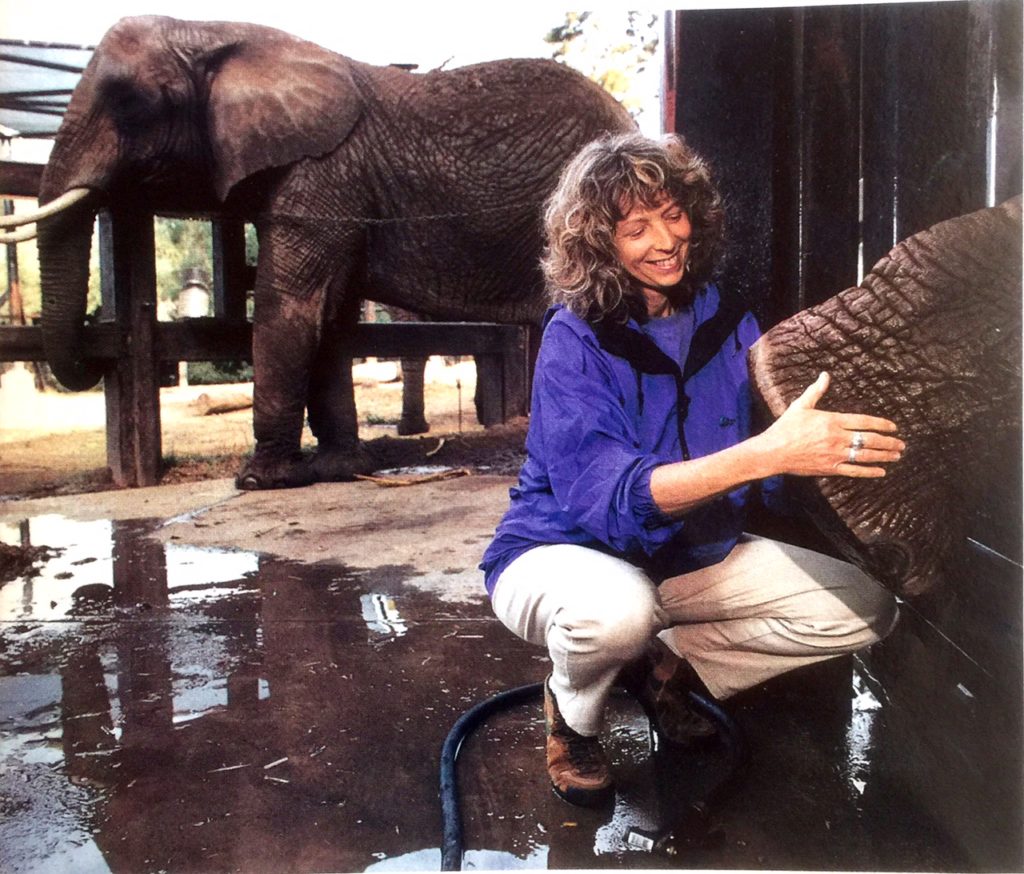

ELKE RIESTERER LIKES TO massage elephants. Twice a month, Riesterer, 51, a massage therapist, drives 90 minutes from her home in Santa Cruz, California, to volunteer her skills at the elephant barn of the Oakland Zoo. On this particular morning, she’s bending over the foot of Smokey, a 27-year-old, 16,000-pound male African elephant, who stands in a steel restraining pen. Smokey lifts his left rear leg backward, ponderously, and slides his massive foot, sole up, over the pen’s lower rung. Riesterer’s fingers press slowly on his padded sole, around his huge toenails, gently but firmly. She speaks quietly to the elephant. Smokey huffs like a giant bellows.

Next Riesterer climbs on a platform, on her tiptoes — Smokey stands nearly 11 feet tall at the shoulders — and rubs castor oil into the dry, cracked edges of his ears. She rubs around his tusks, his checks, the skin around his eyes. As she works, Colleen Kinzley, the zoo’s general curator, watches the big fellow’s every twitch. Smokey’s hose—like trunk, governed by more than 40,000 muscles, could easily slip through the bars and toss the masseuse in the air like a bale of hay. But after three years together, Smokey and Riesterer have a strong rapport.

“He’s a sweetie pie,” says Riesterer, her German accent tempered by 17 years in California with her American husband. “In the wild, elephants walk maybe nine miles a day. In the zoo, they just stand around. There are lots of foot problems, like cracks and infections.” Another problem is boredom, though as zoos go, Riesterer gives this one high marks. There are mud wallows for the elephants to roll around in, scatterings of fruit to be dug out from under rocks and in crevices — ongoing attempts to keep the animals amused.

Her real wrath is saved for circuses. When a circus recently rolled into Sacramento, Riesterer and her fellow members of PAWS — the Performing Animal Welfare Society – passed out leaflets to attendees entering Arco Arena, encouraging them to support legislation banning elephants from circuses and traveling shows.

“Elephants are highly intelligent and highly sensitive,” she says. “We can’t keep them for our entertainment and make them do stupid tricks at circuses.”

As much as she loves working with elephants, humans still form the core of her business. She began working with two-legged clients in 1984 – leaving behind a career as a dental hygienist — when she received her massage therapy certification and opened her own practice. She learned about the benefits of body massage as a teenager in Germany after being diagnosed with scoliosis (curvature of the spine). Then, about four years ago, she attended a workshop led by veterinarian Linda Tellington-Jones, developer of the Tellington-Touch, a massage system used to heal injuries in animals. Riesterer first tried the techniques on her ten-year-old horse, Electra, who was struggling with arthritis. The result: Electra’s vet visits dropped dramatically.

Riesterer next used her magic fingers on a rhino. In 1996, she visited a remarkable elephant and rhino orphanage, on the edge of Kenya’s Nairobi National Park, which treats abandoned and traumatized animals and returns them to the wild. Inside the fenced stockade, she met Scuddy, a former orphanage resident who had hobbled back in With a leg injury that was not responding to treatment.

The orphanage’s founder, Daphne Sheldrick, agreed to let Riesterer try therapeutic massage. She approached the 3,000-pound beast and began talking to her, gently, waiting for the right moment before extending her hand. “I began working around the injury, and the rhino started getting into it. Her head dropped and she leaned into my hand — I could sense a feeling of surrender.” From the legs

and feet Riesterer moved on to Scuddy’s head and ears, never afraid, always respectful. The next day, the six—year-old rhino allowed her to touch her mouth and nostrils. “It’s a dance,” Riesterer explains. “They’ll tell you their body language if a particular touch is appropriate by a glazing over of the eyes, a slowing down of the breath, a big sigh, maybe a little sound like a rumble.”

Eventually, Scuddy was released to the wild, returning with her son, Magnum, for Visits to the orphanage. Since then, Riesterer has massaged a virtual Noah’s Ark of animals — a giraffe, a cheetah, a desert tortoise, dolphins, birds, a mouse, more than a dozen baby elephants, and even, yes, a couple of snakes.

“With patience,” she says, smiling, “you can tune in to anything.”